Simonson et al (2009) presents a review of distance education and begins by identifying four core components of distance education and illustrating how the definition has grown over time. This review includes definitions offered by other scholars (Garrison & Shale, 1987; Perraton, 1988; Rumble, 1989; Keegan, 1996) that vary in small but important ways from the Schlosser et al definition. Comparisons of these definitions appear to illustrate how definitions that attempt to apply a level of specificity to the process run the risk of reduced application in the future. For example, Keegan (1996) identified the “influence of an educational organization both in the planning and preparation of learning materials and in the provision of student support” as one of five main elements of a comprehensive distance education definition. However, I would submit that as technology and user needs change, the premise that distance learning is something that is delivered only by “educational organizations” might become obsolete. Businesses, for example are not typically considered educational organizations regardless how rigorous and well known their training programs have become. Second, it is possible that over time, the activity of distance learning becomes entrenched in the public life that “the provision of student support” is no longer essential. In the foreseeable future, it is possible that students will know how to support themselves or know how to find the resources for their success. So, beyond the philosophical debate about whether these and other component are critical to the definition of distance learning, it does appear to me that the field is ever changing because of the technology, acculturation to the technological norm of daily life, and the user’s need for acquiring education outside of the classroom.

I am a firm believer that technology will continue to change distance education and that these changes will both be impacted by a person’s profession or by how much technical knowledge he/she has. I have just completed my first distance education course and I believe that my experience and knowledge about the process, expectations and meta-cognition about how I work best in this context all add to my ability to learn and produce products of my learning. The increased capacity that develops for the individual learner can also be applied for an entire culture. One only needs to look at the growth in capacity and use of social media technology as a prime example. It is possible that many may have predicted that some senior citizens would be using cell phone to communicate with their friends and families, but fewer would have predicted that their grandparents would be using Facebook and YouTube. The case of online dating can also be instructive here. “Mail order brides” have been more than a social construction in the minds of Americans, but who would have predicted that Internet dating companies would be claiming that one in five relationships begin online. These examples illustrate two important issues. First, as individuals and groups become more capable with technology, the expectations for what can occur changes. Second, technology has demonstrated the ability to remove or reduce the importance of issues of time and space from traditional human interactions that have traditionally been believe to be essential. This brings us to learning, or distance learning and the opportunity to replicate or recreate a learning environment that is closer to or essential the same as the traditional classroom experience (i.e., face to face interaction, group learning, etc). It appears to me that the distance learning experience can become even more like a classroom experiences as video/audio and recording/projection continue to advance. I see a future where “teacher in the classroom” can become teacher (“real” or virtual) in “your room” for the sake of delivering content, supporting learning, and evaluation student performance.

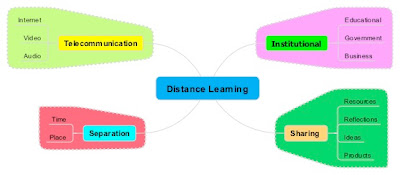

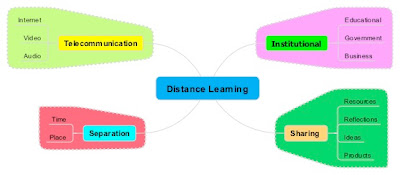

As I reflect on my understanding of distance learning, it’s clear that I primarily focused on the components of “separation of teacher and student” and “interactive telecommunications” that supported the learning environment. This is due in large part to my lack of direct experience with distance learning before my “Instructional Design” courses (Jan–Feb 2011). Prior to that course, I only had indirect knowledge of distance learning through a friend who completed an MBA from Boston University via distance learning. While I’m sure I didn’t hear everything about the Boston University program, my friend only shared that the courses were generic and primarily involved him in the reading articles and writing papers. The learning resources from week one of our “Design Education” course has certainly broaden my perspective to the core components of distance education, the variation of application, and the real and potential growth within the field.

Integrating my limited prior knowledge and experience with the new information I have gained, I currently believe that the Schlosser and Simonson (2006) definition of distance learning is the most useful and provides the flexibility that I believe will be necessary to adapt to growing technologies and user needs.

Moreover, I predict that that distant education will grow because of economic factors and evolve as a “delivery platform.” On college campuses, I have seen evidence that the role of distance education has become more important because of the financial revenue it is producing. For some institutions of higher learner, the non-traditional classroom experience runs counter to their brand. Many of the elite Liberal Arts colleges, Ivy League Universities, and those that aspire to such selectivity and prestige sells, at least in part, the institution’s brand on the unique and special interaction between student and professor. These institutions distinguish themselves from the competitions based of on the intimate learning environment that is fostered by small student-faculty ratios and prominent Ph.D. faculty who are published and funded at the highest level. These elements, to date, are absent from distant learning. However, the perfect storm that is lowered endowment payouts, decreasing federal and state support, and increasing revenue generation form distance education may open the doors at these institution. However, regardless what the most selective institutions do with distance education, the other 95 percent of colleges and Universities are well aware of the financial opportunity available from distance education done well. Georgia Tech University recently described their involvement in distance education in the following manner:

“Distance Learning and Professional Education (DLPE) is a full service educational organization of Georgia Tech that delivers world-class programs and degrees, both non-credit and credit, to six of the seven continents around the globe. During the 2010 fiscal year, DLPE grossed approximately $26.6M in revenue and more than 18,000 students from over 3,300 companies participated in programs Harvard and Yale.”

As more institutions of higher learning become fully involved in distance learning, I believe that the cultural norms will begin to shift because of the value that will be attributed by virtue of perceive and actual experience with learning via distance education.

References

Garrison, D. R., & Shale, D. (1987). Mapping the boundaries of distance education: Problems in defining the field. The American Journal of Distance Education, 1(1), 7-13.

Keegan, D. (1996). The foundations of distance education (3rd ed.). London: Croom Helm.

Perraton, H. (1988). A theory of distance education. In D. Sewart, D. Keegan, & B. Holmberg (Eds.), Distance education: International perspectives (pp. 34-45), New York: Routledge.

Rumble, G. (1989). On defining distance education. The American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 8-21.

Simonson, M., Smaldino, S., Albright, M., & Zvacek, S. (2009). Teaching and learning at a distance: Foundations of distance education (4th ed.) Boston, MA: Pearson.